Wavering Place, A Detailed History

by Katharine Allen of Historic Columbia, funded by a grant from the Richland County Conservation Commission in 2019, edited in part by Weston Adams III and Lisa Boykin Adams

Joel Adams I

Ownership of Joel Adams I

Joel Adams I (1750-1830), a North Carolinian born of a Virginia family, arrived in Richland District in 1768 at the age of 18. In 1773, he married Grace Weston (1752-1832), the daughter of a neighboring planter, and established a 565-acre plantation east of Cedar Creek called Homestead. Over the next 60 years, he acquired the moniker “Joel of All,” based in part on his reputed 25,000 acres of land, which stretched in all directions from Homestead, most notably to the banks of the Congaree River. Upon these lands, Adams and his sons oversaw large-scale logging, agricultural, livestock, and transportation endeavors, all facilitated by the work of hundreds of enslaved men, women, and children. Upon Adams’ death in 1830, his four surviving sons and numerous grandchildren continued to act as stewards of the Adams family’s ancestral lands, ensuring that land, slaves, and profits all passed from one generation to the next.

In 1792, Adams purchased the tract of land known today as Wavering Place from William Heatley, likely because it shared its southern border with Homestead. Joel incorporated the Heatley tract into his Homestead Plantation, and managed the lands together until 1811, when he allowed his son, Dr. William Weston Adams, to establish a separate residence here. Dr. Adams named his new domain Green Tree.

After Joel Adams I’s death in 1830, his four surviving sons and numerous grandchildren continued to act as stewards of the Adams family’s ancestral lands, ensuring that land, profits, and an ever-growing number of enslaved individuals all passed from one generation to the next. As Civil War diarist Mary Boykin Chesnut later wrote, the Adams, along with the Hamptons and the Taylors, became the dynastic planter families of Richland District---“the big fish [who] ate up all the little ones.”

From their grandfather, Dr. Adams’ children inherited Green Tree, an adjoining tract once owned by John Price, and the northern half of the original Homestead tract. Since then, it has been owned by a series of Joel Adams I’s direct descendants, including descendants from four different Adams family lines: the heirs of Dr. Adams (as Green Tree); Frances Tucker Hopkins and her descendants (as Magnolia); Col. James Pickett Adams and his descendants (as Wavering Place); and the Robert Adams II line, who continue to own it today. What follows is a recounting of those who have called this place home.

Occupation and Management under Dr. William Weston Adams and his heirs

William Weston Adams’ graduating class Yale 1806

Joel Adams’ third son, William Weston Adams (1786-1831), graduated from Yale University in 1807 and completed his medical training the following year at South Carolina College (University of South Carolina). Upon returning to lower Richland County, Dr. William Weston Adams (hereafter Dr. Adams) lived with his parents and two of his brothers at Homestead. By then, Homestead Plantation included the parcel of land known today as Wavering Place, with Joel Adams I’s house site being located on the southeastern portion of the land at the current location of St. John’s Episcopal Church. According to the 1810 US Census, Joel Adams I enslaved 75 people of unknown age and gender across Homestead and several other sites; at least some of these men and women would have been among the last Africans to arrive before the close of the Atlantic Slave Trade on January 1, 1808. A few were likely gifted to Dr. Adams once he established his own homestead here, perhaps even those who were already working this tract of land for Joel Adams I.

On November 6, 1811, Dr. Adams married Sarah Eppes Goodwyn (b. 1791). The couple assumed management of this tract, which they called Green Tree, although it remained under the ownership of Joel Adams I. They may have initially lived in the one-story frame dwelling located on the northeastern corner of the property’s main clearing, although it is possible that this structure predates their time here. Sometime in the 1810s, they had a new residence, of unknown style, built on the site of the current Greek Revival mansion, as well as a pair of one-story, brick structures that flanked the rear of the main residence. The western structure stands today; the eastern structure was rebuilt in the nineteenth century, upon the original structure’s brick foundation, and physical evidence points to its use as a smokehouse. At least one of these buildings functioned as a kitchen. The other may have been used for other domestic chores or to house enslaved people working in the main residence.

By 1820, Dr. Adams’ household included 41 people, 34 of whom were enslaved. Twenty-two of these men and women labored in the fields. Others performed domestic chores, took care of livestock, and kept the mansion and its environs well-manicured. Although no narratives survive that describe what life was like at Green Tree, it may have been similar to the setting Charles Ball described in his memoir, Slavery in the United States. Ball was sold by slave traders to a plantation in lower Richland County around 1806. Here he describes his first night:

After it was quite dark, the slaves came in from the cotton-field, and taking little notice of us, went into the kitchen, and each taking thence a pint of corn, proceeded to a little mill, which was nailed to a post in the yard, and there commenced the operation of grinding meal for their suppers, which were afterwards to be prepared by baking the meal into cakes at the fire. The woman who was the mother of the three small children, was permitted to grind her allowance of corn first, and after her came the old man, and the others in succession. After the corn was converted into meal, each one kneaded it up with cold water into a thick dough, and raking away the ashes from a small space on the kitchen hearth, placed the dough, rolled up in green leaves, in the hollow, and covering it with hot embers, left it to be baked into bread, which was done in about half an hour. These loaves constituted the only supper of the slaves belonging to this family; for I observed that the two women who had waited at the table, after the supper of the white people was disposed of, also came with their corn to the mill on the post, and ground their allowance like the others. They had not been permitted to taste even the fragments of the meal that they had cooked for their masters and mistresses. It was eleven o'clock before these people had finished their supper of cakes, and several of them, especially the younger of the two lads, were so overpowered with toil and sleep, that they had to be roused from their slumbers when their cakes were done, to devour them.

We had for our supper to-night, a pint of boiled rice to each person, and a small quantity of stale and very rancid butter, from the bottom of an old keg, or firkin, which contained about two pounds, the remnant of that which once filled it. We boiled the rice ourselves, in a large iron kettle; and, as our master now informed us that we were to remain here some time, many of us determined to avail ourselves of this season of respite from our toils, to wash our clothes, and free our persons from the vermin which had appeared amongst our party several weeks before, and now begun to be extremely tormenting. As we were not allowed any soap, we were obliged to resort to the use of a very fine and unctuous kind of clay, resembling fullers' earth, but of a yellow colour, which was found on the margin of a small swamp near the house. This was the first time that I had ever heard of clay being used for the purpose of washing clothes; but I often availed myself of this resource afterwards, whilst I was a slave in the south. We wet our clothes, then rubbed this clay all over the garments, and by scouring it out in warm water with our hands, the cloth, whether of woollen [sic], cotton, or linen texture, was left entirely clean. We subjected our persons to the same process, and in this way freed our camp from the host of enemies that had been generated in the course of our journey.

Dr. Adams worked as a physician, but most of his income resulted from agricultural and industrial labor and animal husbandry performed by enslaved men and women. Financial records indicate that Dr. Adams had significant debt by the late 1820s, perhaps indicative of a gambling problem or other vice. On May 6, 1829, he transferred ownership of his entire “lot of slaves” to his father, who valued them at $12,375, in exchange for assumption of this debt. Despite assuming ownership of his son’s property, Joel Adams I allowed him to continue to use their labor for his own financial means and comfort. Therefore, over the next year, Dr. Adams effectively lived at and oversaw the labor on a plantation that belonged completely to his father. This illusion was reflected in the 1830 census, enumerated in June 1830, which recorded Dr. Adams as the owner of 50 enslaved individuals, despite them being legally owned by his father. Among them were 19 children under the age of 10 who were not alive when the 1820 census was taken; they would have been born on Green Tree.

Joel Adams I died in the summer of 1830. His will, recorded in October 1829, primarily divided his estate amongst his eldest sons, James (b. 1776), Joel Adams II (1784-1859), and Robert (1793-1850); the heirs of his deceased children, Sarah Adams Tucker (1788-1809) and Henry Walker Adams (1790-1815); and the heirs of Dr. William Weston Adams. Although Dr. Adams continued to manage Green Tree, its main tract, as well as an adjacent tract acquired from John Price and additional land near Adams’ Mill on the Congaree River, now belonged to his children and would be administered by his brother, Robert Adams I. Furthermore, Dr. Adams could continue to oversee the enslaved people he sold to his father, but only if he did so “prudently.”

Dr. Adams died in 1831. In the appraisal of his estate, his brother, James Adams, and nephew-in-law, David Thomas Hopkins (1802-1836), noted that 48 men, women, and children “were conveyed by William W. Adams[,] deceased[,] to Joel Adams[,] deceased[,] and by the said Joel Adams devised to the children of said William W. Adams and were appraised by us as property considered without situation.” They were collectively valued at $12,995, slightly more than when Dr. Adams sold them to his father two years prior. Two other women, “Matilda and child Amanda,” were appraised separately, likely because Dr. Adams had purchased them after entering into the 1829 financial arrangement with his father.

Sarah Eppes Goodwyn Adams allowed her brother-in-law, Robert Adams I, to administer her husband’s estate on behalf of herself and her surviving children. Among the family’s recorded expenditures was medical care for her eldest son, John Goodwyn Adams (1814-1833), who was killed in a duel while a student at South Carolina College ($43). Other expenditures included painting the main residence ($194), paying past debts and current tuition for the children’s school and boarding (approximately $264), paying overseer Willy Jones for his labor and the hiring of eight enslaved people ($270), and resolving a debt incurred by her husband for the purchase of a “negro woman and child” from W.C. Ferrill ($561.75). This family was likely Matilda and Amanda. To pay for these expenditures, Robert Adams I used the proceeds from 48 bales of cotton (approximately $1,280) and an $800 payment owed to his nieces and nephews from Joel Adams I’s estate.

Receipt for Matilda and Amanda

In 1833, county ordinary James S. Guignard authorized a public auction of goods and chattel from Dr. Adams’ estate, which was held at Green Tree. Matilda and Amanda were auctioned first. Joel Adams II purchased them for $350 “for the heirs of” his brother, Dr. Adams. Although the enslaved mother and daughter remained at this site, they still underwent the humiliating and frightening experience of the auction block. Joel Adams II also purchased all of the estate’s mules, save one, 12 head of cattle, 40 sheep, 70 hogs, three horses, and two carts, for his brother’s heirs. In effect, this sale raised money for Dr. Adams’ children ($1,010) while granting them continued ownership of the property.

The 1840 census recorded Dr. Adams’ eldest surviving son, Henry “Harry” Walker Adams (b. 1816), as the head of household. The eight-member household included his wife, Rebecca Johnston, son, William Weston Adams II, mother, Sarah Eppes Goodwyn Adams, and a few siblings. Together, the family enslaved 74 individuals, including 17 children under the age of 10 who were not alive during the enumeration of the last census and at least seven more who were purchased by the family after the death of Dr. Adams. This entire branch of the greater Adams family left South Carolina by the mid-1840s for new land opportunities in Alabama, Louisiana, and Texas. It is unknown if the Adams siblings, in an effort to divide their father’s estate equitably, separated enslaved families before their migration to the west, but records show that most, if not all, of these enslaved people were taken out of the state.

Three members of Dr. Adams’ immediate family moved to Lowndes County, Alabama, to take over a distant planation that Joel Adams I had purchased as an investment, but had never visited. According to the 1850 census, both Harry Adams and his sister, Sarah Adams Lowe (b. 1821), had children born in that state after 1845. Sarah Eppes Goodwyn Adams lived with this daughter and her son-in-law. Between the three families, they enslaved 47 people. Another sister, Grace Adams Taylor (1823-1896), married James H. Taylor (1824-1885), a descendent of Thomas Taylor, and moved to Montgomery, Alabama. The couple enslaved 82 people. Another brother, Joel Adams III (b. 1816), moved to New Orleans, Louisiana, and another sister, Martha Adams Myers, (b. 1812) moved to Texas. Records do not show how many people they enslaved. (This Joel Adams III appears as the hunting companion of Maxcy Gregg’s in Maxcy Gregg’s Sporting Journals, 1842-1858.)

Ownership and Management under Frances Martha Tucker Hopkins

Frances Martha Tucker Hopkins image-Lower Richland Planters

The heirs of Dr. William Weston Adams sold this tract of land sometime between 1843 and 1855 to their first cousin, Frances “Fannie” Martha Tucker Hopkins (1806-1864), who was a member of the Adams family through her mother Sarah Adams Tucker, the sole daughter of Joel Adams I. This purchase adjoined another tract of land owned by Frances Hopkins (hereafter Hopkins) immediately to the west, which was purchased for her by the administrator of her husband’s estate. She built this Greek Revival residence, called Magnolia, by 1855. It replaced Dr. Adams’ residence, which family tradition states was destroyed by fire. It is possible that Hopkins and her two sons lived in the one-story residence while construction took place, or that they remained at Cabin Branch, her deceased husband’s ancestral home.

Even before she acquired this site, Frances Hopkins was already wealthy. Her parents, Sarah Adams Tucker (1788-1809) and Reverend Isaac Raiford Tucker (1772-1811) died when she was a child, leaving her and her siblings substantial property. The Tucker siblings were subsequently raised by their maternal grandparents, Joel Adams I and Grace Weston Adams, at Homestead, which adjoined Green Tree to the south. In 1826, Frances married David Thomas Hopkins (1802-1836), the eldest surviving son of John Hopkins II (1765-1832). The following year, she sold “wench Peggy and child Jacob” to William Quick for $400 (see image 2). It is unknown how she acquired Peggy, but the sale of the mother and child points to a possible relationship between them and her new husband.

In 1830, Frances inherited a portion of the massive estate created by her grandfather, Joel Adams I, and two years later she inherited wealth from the estate of her brother, Joel A. Tucker (1798-1832). Her father-in-law, John Hopkins II, also died in 1832, leaving her husband substantial lands in lower Richland County and a saw mill. Family tradition states that before his death, John Hopkins II also purchased land in Marion County, Florida, for his son in hopes that periodic visits would help with the latter’s tuberculosis. It is likely David Hopkins contracted it from his wife, who by then had lost several siblings to the disease.

David Hopkins died in 1836, leaving behind his wife and two young sons, John David Hopkins (1827-1866) and James Tucker Hopkins (1831-1863). His will granted Frances numerous tracts of land, totaling more than 800 acres, spanning both banks of Cabin Branch and several squares of the abandoned town of Minervaville. Established in 1785 as the site of Richland County’s first courthouse, the name was derived from its later use as Minerva Academy, a school that David Hopkins attended in his youth. His will also stipulated that money acquired from repaid debts and the sale of his shares in the James Boatwright steamboat should be used to buy the rest of the town for his wife’s use. To his sons, he left substantial tracts of land and the sawmill to be shared jointly; this property was all inherited from his own father, John Hopkins II.

The 102 people that David Hopkins enslaved at the time of his death were divided equitably between his wife and sons. He made special provisions for several people who would find themselves transported to this site from neighboring Cabin Branch. Among them were “a mulatto girl named Massy, and my cook named Caty, and their increase,” whom he lent to his wife for the remainder of her life. His sons were each gifted half of his “blooded stock of horses” and one “negro boy” as a body servant. They were named Joe and Charles.

In June 1843, Frances Hopkins petitioned for guardianship of her sons’ inherited estate, valued at $60,000. That same month her own tract of land was resurveyed; it had grown to 1,188 acres. To its immediate east was Green Tree, Dr. Adams’ plantation, then under the ownership of his children. She likely purchased Green Tree within the next two or three years, as Dr. Adams’ children moved out of state. When the entirety of Hopkins’ property was resurveyed in 1855, its 2,083 acres stretched from the western bank of Cabin Branch to the land east of Cedar Creek, where the main residence stands. Upon Frances’ arrival at Green Tree, her closest neighbors were also her family. Her childhood home, Homestead, was less than a mile to the south, and Grovewood, owned by her sister and brother-in-law, Christian Grace Tucker (1796-1854) and William Weston II (1795-1848), was less than a mile to the east. She rechristened Green Tree as Magnolia, although it is unclear if this change took place before or after the destruction of the residence built by Dr. William Weston Adams.

Although very few documents survive from the Hopkins’ life during the 1840s, the ones that do remain create a picture of extravagant spending. As teenagers, John D. and James T. Hopkins regularly purchased items from the clothier Antwerp & Frank, who imported goods from New York and Europe. Items billed to the estate of David Hopkins by John D. Hopkins included a “Black French Marine Coat” ($18), a “Marino Frock Coat” ($25), a “Cashmere Vest” ($14), and a “Coat, Pants and Vest” ($46). Regular purchases of cravats, gloves, “half hose,” pantaloons, vests, and suspenders indicate the fashion trends of the wealthy. Purchases of suspenders for friends and a “coat for friend Gist” indicate either John’s generosity or his lack of concern over money. (“Gist” is almost certainly States Rights Gist (1831-1864), a graduate of South Carolina College who married John’s second cousin, Jane Margaret Adams (b. 1841), and died while serving as a brigadier general in the Confederate Army.) In 1843, the brothers’ bill at this clothier ran several hundred dollars. The family continued to spend in the early 1850s, with Frances Hopkins purchasing six dozen silver spoons and several silver serving pieces ($338) from T.W. Radcliffe & Co. in 1853.

Throughout the late 1840s and early 1850s, the individuals enslaved by Hopkins and her two sons may have lived and labored at several locations. Chief among them was the former town of Minervaville, which became known as “Fannie’s Quarters.” Some domestic laborers would have lived in proximity to the family’s residence, likely in one of the structures that still stands on the property or in the basement of the residence itself. Others would have lived in cabins on the immense tracts inherited by John D. and James T. Hopkins. Bills for medical care from 1847 and 1855 provide little insight into their lives (each visit or prescription cost $1) but do document the survival of individuals, such as David, Rachel, and Epsy, more than a decade after their former owner’s death. For example, in 1855, Hopkins paid $1 for “extracting Epsy’s tooth.” Epsy was one of several individuals once enslaved by David Hopkins who lived to see emancipation nearly three decades later. A woman named Charlotte fell ill in 1855, but appears to have survived. Like Epsy, she is named in Frances Hopkins’ will.

According to the 1850 census, Frances Hopkins’ land was valued at $18,000. (Her entire real estate was valued at $24,000, which would not have included enslaved individuals.) About one-third of the acreage was improved. Over the previous year, enslaved laborers grew cotton (87 bales) and enough food to feed themselves and the plantation’s livestock: corn (1,800 bushels), sweet potatoes (700 bushels), peas and beans (150 bushels), and hay (14 tons). They also tended bee hives for honey and beeswax (31 pounds), 23 milk cows (300 pounds of butter), 33 sheep, 172 swine, and 82 heads of cattle. That year, the census recorded 76 enslaved people whom belonged to Hopkins. Nearly half (35), were children under the age of 14, meaning that they were born to people inherited by Hopkins from her husband. John D. and James T. Hopkins’ combined property (2,604 acres) was valued at $34,000 ($40,000 when accounting for livestock). Nearly forty percent of the acreage was improved. They owned more horses and mules than their mother, but fewer cattle, swine, and sheep. They focused on cash crops, including cotton ( 114 bales), corn for livestock fodder (3,000 bushels), and hay (14 tons). They also grew peas and beans (150 bushels) and sweet potatoes (400 bushels) that would have supplemented the corn given to their enslaved workers. That year, they enslaved 86 people, 32 of whom were children under the age of 14, and thus born to individuals the brothers inherited from their father.

In 1850, John D. Hopkins married Octavia Chappell (1829-1882). The couple lived at Chappell Cabin Branch, where they raised four children. It is likely that at least some of the people he enslaved would have left this site to live at the Chappell family home. The following year, James T. Hopkins married Charlotte Caroline Adams (1830-1854), his first cousin once removed. Like Frances Hopkins, Charlotte Adams was a granddaughter of Joel Adams I and had recently inherited substantial property following the death of her father, Robert Adams I (1793-1850), whose estate was valued at $52,000 in 1850. (Her mother, Charlotte Belton Pickett Adams (d. 1833), died when she was a child.) Robert Adams I’s estate, which was largely inherited from his own father, Joel Adams I, included Homestead, the Adams family’s ancestral property to the immediate south of Magnolia. Given that Charlotte Adams had three older brothers, Dr. Joel Belton Adams (1824-1853), John Pickett Adams (18225-1874), and James Pickett Adams (1828-1904), a younger brother, Robert Adams II (1832-1882), and a half-brother, Jesse Reese Adams (d. 1882), all whom received portions of the estate in nearly equal amounts, it remains unclear whether Charlotte and James T. Hopkins would have lived at Homestead, where her step-mother continued to reside. Regardless, after the death of her eldest brother, Dr. Joel Adams, both John and James Pickett Adams continued to administer her portion of their father’s estate. Following Charlotte Adams Hopkins’ unexpected death in 1854, her surviving children inherited 37 people, as well as their earnings from being hired out to other owners. They also inherited money from the sale of “Yellow William” in February 1855 and the earnings of “Bob Ruffle,” who died sometime in the spring of 1855. This transfer of property and money occurred in the summer of 1856. The men, women, and children inherited from her estate may have lived at Magnolia for a period of time (if they did not already), as Frances Hopkins helped care for her own grandchildren.

On November 24, 1858 James T. Hopkins entered into a contract with his brother-in-law, James Pickett Adams, in which he agreed to pay $34,000 for 50 enslaved people. The following day, he paid $12,000 for 20 of these individuals; it is unclear if the rest remained with James Pickett Adams or were transferred to James Hopkins on his credit and that of his mother. That same day, the two men entered into a separate agreement, in which Adams agreed to loan Hopkins $11,000 at seven percent interest, of which half of the principle was due by 1864. Hopkins’ brother, mother, and cousin, Moultrie Weston, all signed as guarantors. By 1860, James T. Hopkins had remarried and moved his family to Marion County, Florida. Although the name and size of his lands remain unknown, his combined personal and real estate holdings were valued at $175,000, indicating a truly massive operation. He transported 124 enslaved people, including most, if not all, of those he inherited or purchased since the 1830s, as well as their descendants, to Florida. They lived in 31 cabins on the estate and were overseen by H.L. Dunn, also a native of South Carolina. James’s brother, John D. Hopkins, also transported 40 enslaved people to Marion County, Florida, where they were overseen by Samuel S. Hendrick, also a native of South Carolina. His estate there was valued at $40,000. Neither John D. Hopkins nor his family were recorded in Richland District in 1860, but it is likely that they resided with Frances at least some of the time, who was also missed by the census taker. That year, the slave schedule recorded 80 people enslaved by “Fanny” Hopkins.

In 1863, James T. Hopkins died while serving in the Confederate Army. Prior to his death, he had paid his brother-in-law, James Pickett Adams, $1,661,75 of the 1858 bond. Frances Hopkins died a few months later, in January 1864. Hopkins’ will, made days before her death, divided her property between her surviving son, John D., and the children of James. It also made a special provision dictating that five enslaved men and women, Cicero, David, Isabel, Charlotte, and Judy, be kept on the plantation. Local planter D.W. Ray served as the estate’s executor. At the time of her death, it included 83 enslaved men, women, and children, $2,000 in household wares, more than 200 head of livestock, and ample crop provisions. However, transactions over the following year illuminated a plantation trying to stay solvent at the end of the Civil War. Hopkins’ estate initially received money from the government, both by selling cattle and wooden barrels and by cashing in her substantial Confederate Bonds.

Of course, the South changed dramatically after Hopkins’ death. Like many of the Adams family’s plantations, Magnolia’s economic framework, which relied on the ability to buy and sell enslaved bodies and the ability of those bodies to labor and reproduce, collapsed at the end of the Civil War. On top of losing its human capital, the estate lost thousands of dollars in Confederate Bonds and accrued thousands of dollars in taxes. Frances’s surviving son, John D. Hopkins, died in 1866. His brother-in-law, Paul Chappell brought his body from Charleston to be buried in the family cemetery. He also took charge of his estate, which he swore did not value more than $2,000. By the time Frances Hopkins’ estate was settled in March 1868, it owed back taxes for several years, $3,000 to a Mr. Shelton for “negro shoes,” wages to her overseer, and small sums for medical bills and other supplies. There is no record of her continuing payments on her son’s debt to James Pickett Adams. Her surviving grandchildren, the great, great-grandchildren of Joel Adams I, had inherited this site, but by then it was in unmanageable debt.

Ownership of James Pickett Adams and Margaret Crawford Adams

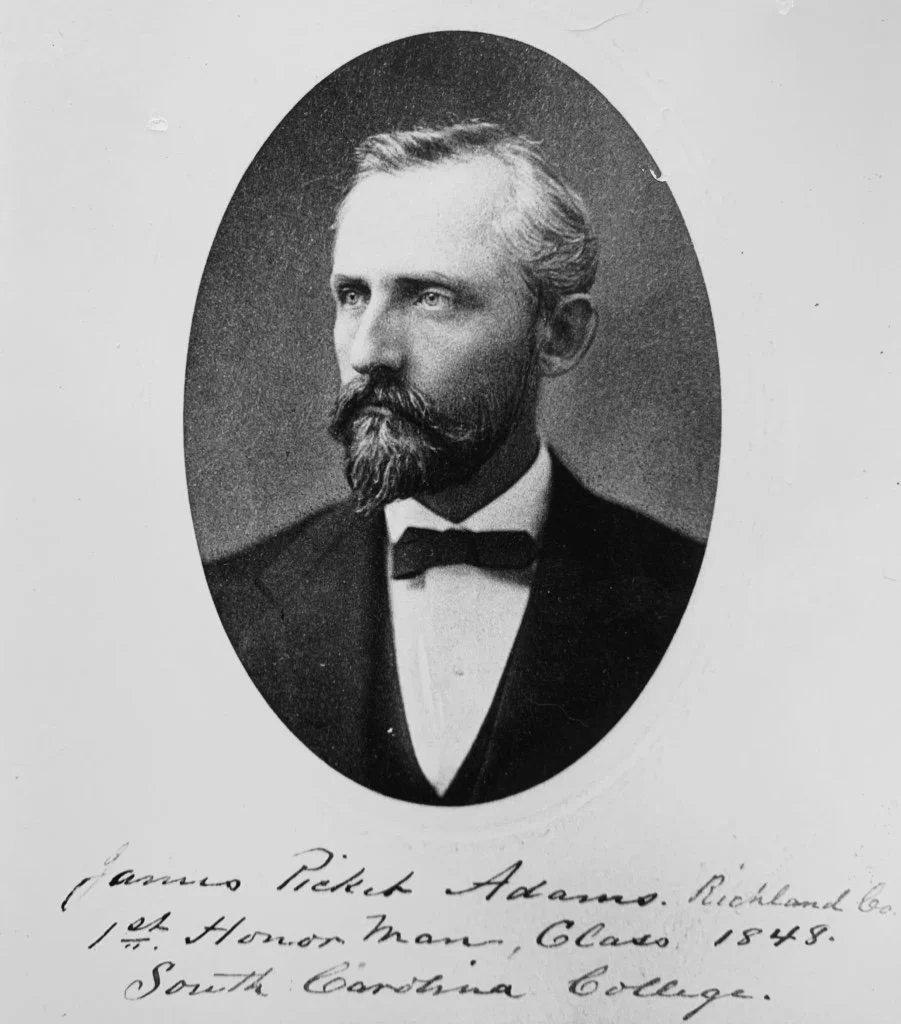

James Pickett Adams

In December 1868, Colonel James Pickett Adams (1828-1904), uncle of James T. Hopkins’ surviving children (and Frances Hopkins’ first cousin), used the unpaid bond from 1858 to force a sale of the entire estate. Available at auction was the Magnolia tract of Frances’s land (400 acres), located primarily to the east of Cedar Creek; the Minervaville tract (1,800 acres), located to the west of Cedar Creek; and the contents of the house. The auction took place the following month. James P. Adams (hereafter Col. Adams) purchased both tracts of land for $11,250 and most of the contents of the house for $571.30, less than what the heirs of James T. Hopkins owed him. In total, the sale grossed more than $12,350, although it’s unlikely that Frances Hopkins’ grandchildren received any proceeds. However, Col. Adams’ purchase of Magnolia kept the plantation in the Adams family; by then, it had passed from Joel Adams I to his grandchildren by William Weston Adams, then to his granddaughter by Sarah Adams Tucker and her children and grandchildren, and finally to his grandson Col. Adams, son of Robert Adams I.

Col. Adams and his wife, Margaret Crawford Johnston Adams (1830-1909), and their only child, Elizabeth “Lillah” Adams (1850-1937), moved to Magnolia, which they renamed Wavering Place. The following year, Lillah Adams married Theodore Brevard Hayne (1841-1917) at the mansion. Hayne was descended from a prominent lowcountry family. Like his father-in-law, Hayne was a veteran of the Confederate Army.

A description on the back of a photo of James Pickett Adams, most likley written by his daughter Lillah after his death that mentions Charlie Brown

First honor graduate USA

intended to live in Europe ??

organized a company of US Soldiers

fought in Virginia and was wounded and brought home by “Old Cholly”, his negro body servant

returned to his plantation

James Pickett Adams USC of Columbia SC and of Wavering Place Congaree Richland County SC

Father of Elizabeth("Lillah" Adams) (Mrs. T.B. Hayne)

traveled in Europe 18?? came home to fight

The Adams brought with them at least two families they once enslaved: the Browns, headed by Charles Brown (b. 1835), and Peter Howell Adams (b. 1834 see image 11). Peter Adams was willed to James Pickett Adams following the death of his older brother, Dr. Joel Belton Adams, before emancipation. Local tradition states that Peter Adams was an Adams descendant, born to one of the Joel Adams and an unnamed enslaved woman. Peter’s father was likely Joel Adams II of Elm Savannah Plantation, and if so, Peter would have been Colonel Adams’ first cousin. After emancipation, he married twice and lived until 1926.

Charles Brown’s lineage was a point of pride to his former owners, as was the Browns’ perceived devotion after emancipation. It is impossible to know how they felt about the Adams. Like most freedmen, the Browns had few economic opportunities beyond the employment offered by their former enslavers. Furthermore, a decades-long relationship between Charles Brown and the Adams would have created deep emotional ties. In an act of mythmaking, Lillah Adams Hayne used the stories of these two families as proof that individuals who were once enslaved remained in the employ of their former owners must have felt that their previous enslavement was not bad, that they had been treated well, and that they continued to love their former owners.

According to Lillah Hayne, Charles Brown, whom she called Charlie, was a third-generation enslaved cook. His grandmother, Therese, and his mother, Selina, arrived in what Hayne called a “romantic incident,” in which the ship transporting them across the French West Indies was destroyed by a great storm. The mother and daughter were lashed to a raft that drifted to Charleston, where they were sold as slaves. Therese became a well-known pastry chef that attracted the attention of planter Samuel Johnston, who purchased her daughter, Selina, to work in his home in Fairfield District. When Johnston’s own daughter, Margaret, married James Pickett Adams in 1849, they received both Selina, who by then “was the mother of many children,” and her son, Charles. The Adams took the mother and son to Richland District, separating them from their family. According to Hayne, Charles Brown “was a master of pots and the kitchen was his kingdom, where he reigned supreme.” Beginning in 1869, his place of work was the kitchen at Wavering Place, which stands today. There Brown “initiated his daughter Katy in all culinary mysteries, making a Wavering dinner an epicure’s delight.” Katy, later known as Katy or Katie Jackson, in turn, trained her own son Louis (or Lewis) Adams, who worked in the home of Hayne’s daughter, Theodora Brevard Hayne Black (1889-1929).

Lillah Adams Hayne shared these memories in “Katy: A Tribute,” published in The State newspaper on August 25, 1931 See Image 6, just a few days after the death of “her faithful servant.” The piece ostensibly served as a memorial to Katy Jackson’s cooking talent—"making Southern gumbo, fryin[g] crisp brown chicken, roasting a Christmas turkey, boiling pink ham, baking delicious biscuits, crumbling corn bread, candying yellow yams”—but functioned effectively as a lament for the old South’s “bygone days.” Hayne declared that the last “retainers” of that time were the formerly enslaved, “with their traditional love and respect for the master and mistress,” a dynamic that was “alas, fast disappearing!” This tribute was the only obituary published for Katy Jackson, and it used neither her last name nor the names of her mother or other children. In death, as in life, she was an instrument serving the Adams family’s needs and desires.

Hayne shared the story of her family’s cooks once before, in 1928, following the death of Katy’s son, Lewis Adams. (His name appeared frequently as Lewis and Louis.) In that piece, published in The State, she declared, “Son of Scorner of Freedom, Lewis Adams Dies at Hospital.”(see image 8) According to Hayne, Lewis was born at Wavering Place, “where his mother and grandmother lived, never claiming the freedom given them by their liberator, Abraham Lincoln.” She chose not to share the names of these family members.

Census records provided a different portrait of Charles Brown and his descendants. In 1870, Charles “Charlie” Brown (34) and his wife, Sarah (35), who worked as a domestic servant in the household, were the parents of six children: Robert (13), Mary (10), Samuel (9), Frederick (7), Katy (5), and James (2). The 1880 census recorded a much smaller household: Charles Brown (48) and three sons: Samuel (17), Frederick (15), and Butcher (6). It is likely that some of the children had married and that other household members had died or were living elsewhere.

Although the 1890 census does not survive, in 1891, Col. Adams made a special plea on behalf of Charles Brown’s son, Frederick Brown, which was published in the March 22, 1891 issue of The State newspaper (see image 12):

“The subscriber, as one of the petitioners, desires to state that this testimonial to the character of Fred. Brown, contained in the petition, comes principally from citizens, white and colored, who reside in that section of Richland where the prisoner lived all of his life until he moved to Lexington a few years ago. In fact, the subscriber may say that the prisoner was brought upon his land, and he never knew a more sober, peaceable and industrious colored man.

He and his father’s family were slaves of mine, and remained with me after emancipation. His father and several of the family are still in my employment. They have always been respectful, true and loyal to the white people.”

Governor Ben Tillman surprised Lexington County officials when he announced the commutation of Frederick Brown’s sentence from death to life in prison. In his remarks, he did not question whether Brown was guilty but did not believe that a “peaceable man” would commit pre-meditated murder. He also believed that self-defense deserved the same punishment as an act performed “in the momentary heat of passion.” While Col. Adams assuredly saved Frederick Brown’s life, Brown still suffered at the hands of an unequal justice system. Brown spent the rest of his life at the Central Correctional Institute on the Congaree River. His younger brother, James, named his own son in his honor.

The 1900 census listed Katy Jackson, born March 1865, as the head of the household immediately following that of Margaret and John Pickett Adams. She had been married 12 years and had nine children, eight of whom survived and continued to live with her. Half carried the last name Adams, and half carried the last name Jackson. For the next twenty years, Katy Jackson lived with or near her younger brother, James Brown, her sons Lewis Adams and Charles “Charlie” Adams, and daughter Mary Jackson, and their families. They worked for James Pickett Adams until his death in 1904, his wife, Margaret, until her death in 1909, and then for Lillah Adams Hayne’s son, Dr. James Adams Hayne (1872-1953) during the 1910s and 1920s. Although Louis Adams could certainly cook, census records recorded him as a farm laborer and as working at a sawmill in lower Richland County through 1920. If Louis ever worked in the home of Dr. Hayne’ sister as a cook, Theodora Hayne Black (1889-1929), then he did so briefly before his death in 1928.

Ownership of the Hayne Family

James Adams Hayne(center with straw hat) with family

image-Hayne Family

Although her writing conveyed a lifelong relationship with the family of Charles Brown, Lillah Adams Hayne spent most of her adult life in Greenville. Instead, it was her son, Dr. James Adams Hayne (1872-1953), who would raise his own children at Wavering Place. After graduating from the Medical University of South Carolina in 1895, he eventually settled in Blackstock and married Fannie Douglas Thorn (1874-1969). The family remained there until 1904, barring a short stint during which Dr. Hayne served as a doctor during the Spanish American War. He held medical positions for the federal government in Washington D.C. and then Cheyenne, Wyoming, before being elected the State Health Officer of South Carolina in 1911, a position he held until 1944. After his appointment, his family took up residence at Wavering Place for the first time. The Haynes raised nine children there, including three doctors. His son, Theodore Brevard Hayne was known for his research on yellow fever, a disease that sadly took his life while working in Africa. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Wavering Place was the scene of numerous weddings and barbecues. It also served as a refuge for other family members, including Admiral George “Boney” Davis, who spent summers there after his mother’s death. In particular, Davis remembers Charlie Adams, who lived with his wife, Peaches, in the two-room, wooden structure on the northern side of the main clearing. As a son of the Adams’ former cook, Katy Jackson, it is possible he called this structure home for most of his life.

At the time of his death in 1953, Dr. Hayne had 22 grandchildren and 4 great-grandchildren. Charlie Adams lived on the property until the 1950s, and upon his death in 1962 he was laid to rest at New Light Beulah Baptist Church Cemetery alongside his mother, Katie Jackson, and many of the families once enslaved at Wavering Place.

Dr. Hayne’s widow remained in residence until her death in 1969, as did one of their daughters, Lillah Adams Hayne (1902-1992), until a few years before her death in 1992. By then, the property was owned by more than 50 heirs. In 1986, Dr. Julian Calhoun Adams, a descendant of James Pickett Adams’ younger brother, Robert Adams II (1832-1882), bought out his cousins and in 1992 established a native plant nursery. He also began a restoration of the main residence, which was in disrepair. In 2013, his own nephews, Robert Adams VI and Weston Adams III, purchased the property and continued this work. Wavering Place is now one of a few intact antebellum plantation sites in Richland County, and as such its stewards remain dedicated to the preservation of its landscape, structures, and the stories of all the people who once lived here.

Dr. Julian Calhoun Adams photographed at Wavering Place by Rosa Shand for Garden and Gun Magazine 2008

Download this document for full list of sources and footnotes